Taxing Unrealized Capital Gains

Understanding the Debate on Taxing Unrealized Capital Gains

In the realm of tax policy, the concept of taxing unrealized capital gains has emerged as a topic of significant debate and interest among economists, policymakers, and investors alike. This article aims to delve into the intricacies of this issue, exploring its potential implications and the ongoing discussions surrounding it.

Capital gains represent the increase in value of an asset, such as stocks, real estate, or collectibles, from the time of purchase until its sale. When an investor sells an asset at a higher price than its original cost, they realize a capital gain, which is typically subject to taxation. However, the debate intensifies when considering the taxation of unrealized capital gains—those gains that have accrued but remain unrealized due to the asset still being held by the investor.

Proponents of taxing unrealized capital gains argue that it would address several economic and social concerns, while opponents raise valid counterpoints regarding the potential complexities and unintended consequences. As we navigate through this complex issue, we will examine the arguments on both sides, explore real-world examples, and discuss the potential impact on investors, markets, and the overall economy.

The Case for Taxing Unrealized Capital Gains

Advocates for taxing unrealized capital gains put forth several compelling arguments, each with its own merits and implications.

1. Revenue Generation and Equity

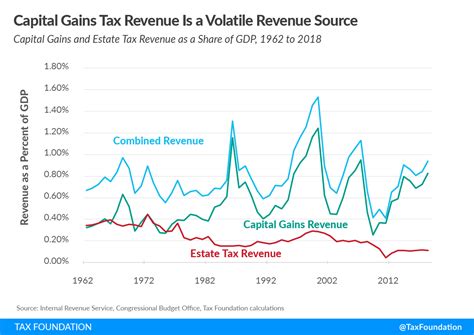

One of the primary justifications for taxing unrealized capital gains is the potential for significant revenue generation. As the value of assets, particularly those held by high-net-worth individuals and institutions, appreciates over time, the accumulated unrealized gains can be substantial. Taxing these gains could provide a substantial boost to government revenue, enabling the funding of various public initiatives and services.

For instance, consider the case of a tech entrepreneur who held onto a significant stake in their company’s stock for several years, witnessing its value soar. The unrealized capital gains on this investment could amount to millions of dollars, which, if taxed, could contribute significantly to government coffers.

2. Addressing Wealth Inequality

The concentration of wealth in the hands of a few is a growing concern in many societies. Proponents argue that taxing unrealized capital gains could help redistribute wealth more equitably. By taxing gains as they accrue, regardless of whether the asset is sold, the government can capture a portion of the wealth generated and use it to benefit a wider segment of the population.

In practice, this could mean taxing individuals with large unrealized capital gains at a higher rate, similar to the concept of a wealth tax. For instance, a progressive tax system could be implemented, where the tax rate on unrealized capital gains increases as the total value of unrealized gains exceeds certain thresholds.

3. Preventing Tax Avoidance

Currently, individuals can defer capital gains taxes by not selling their assets, a practice known as “tax avoidance.” This allows investors to defer taxes indefinitely, potentially until their death, at which point the taxes may be forgiven.

By taxing unrealized capital gains, the government can prevent this form of tax avoidance. Investors would be required to pay taxes on the accrued gains even if they choose to hold onto the assets. This approach could encourage investors to be more active in their investment strategies, potentially leading to a more dynamic and efficient market.

The Counterarguments and Concerns

While the arguments in favor of taxing unrealized capital gains are compelling, there are valid counterpoints and concerns raised by opponents.

1. Complexity and Administrative Burden

One of the primary criticisms of taxing unrealized capital gains is the potential complexity it introduces into the tax system. Tracking and valuing unrealized gains for a wide range of assets, including stocks, real estate, and collectibles, would require significant administrative resources.

Additionally, the valuation of assets can be subjective, leading to potential disputes between taxpayers and the tax authorities. This complexity could result in increased compliance costs for both taxpayers and the government, potentially outweighing the benefits of additional revenue.

2. Impact on Investment and Economic Growth

Opponents argue that taxing unrealized capital gains could discourage investment and hinder economic growth. If investors face the prospect of paying taxes on unrealized gains, they may become more cautious in their investment strategies, opting for lower-risk, lower-return investments or even withdrawing from the market altogether.

This could lead to a reduction in capital available for investment, potentially stifling innovation and economic growth. Moreover, it could disproportionately affect certain industries, such as venture capital and private equity, where long-term investments are common.

3. Double Taxation and Fairness

Taxing unrealized capital gains could lead to instances of double taxation, where the same gains are taxed twice. For example, consider a business owner who has accumulated significant unrealized gains in their company’s stock. If these gains are taxed while the owner still holds the stock, and then the stock is later sold, the capital gains from the sale would also be taxed.

This double taxation could be seen as unfair, as it would effectively penalize individuals for the appreciation of their assets. Additionally, it could create a disincentive for business owners to reinvest their profits into their businesses, potentially hampering growth and innovation.

Real-World Examples and Potential Implications

Several countries have experimented with taxing unrealized capital gains, with varying degrees of success and controversy.

Australia’s Experience

Australia implemented a tax on unrealized capital gains for certain assets, including real estate, in 1985. The tax was levied annually on the increase in the value of the asset, regardless of whether it was sold. However, the tax was soon repealed due to administrative complexities and concerns over its impact on the property market.

This experience highlights the challenges and potential unintended consequences of taxing unrealized capital gains. While the tax generated some revenue, it also led to a decrease in investment and a slowdown in the property market, particularly for high-end properties.

France’s Wealth Tax

France has a wealth tax, known as the Impôt de Solidarité sur la Fortune (ISF), which includes a component for taxing unrealized capital gains on certain assets, primarily financial assets. The tax applies to individuals with a net worth exceeding €1.3 million.

The ISF has been controversial, with critics arguing that it discourages investment and entrepreneurship. However, supporters point to the tax’s role in redistributing wealth and funding public services. The tax has undergone several reforms over the years, with the current government reducing the tax rate and raising the exemption threshold.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities

The debate surrounding taxing unrealized capital gains is multifaceted, with valid arguments on both sides. While the potential for increased revenue and wealth redistribution is attractive, the complexities and potential negative impacts on investment and economic growth cannot be ignored.

As policymakers consider this issue, a nuanced approach is necessary. This could involve targeted taxes on certain assets, such as high-value real estate, or reforms to the current capital gains tax system to address tax avoidance. Additionally, exploring alternative methods of wealth redistribution, such as inheritance taxes or wealth taxes on net worth, could be worth considering.

Ultimately, the decision on whether to tax unrealized capital gains will have significant implications for investors, markets, and the broader economy. It is a delicate balance, and careful consideration of the potential outcomes is essential.

FAQ Section:

How does taxing unrealized capital gains differ from traditional capital gains tax?

+Traditional capital gains tax is levied on the profits realized from the sale of an asset, while taxing unrealized capital gains involves taxing the appreciation in value of an asset even if it is not sold. This means that the tax is triggered by the asset’s increased value, regardless of whether the owner decides to sell it.

What are some of the challenges associated with taxing unrealized capital gains?

+Taxing unrealized capital gains can be administratively complex, as it requires the valuation of various assets, including stocks, real estate, and collectibles. Additionally, it may lead to double taxation if the gains are taxed both when unrealized and when the asset is eventually sold. This could discourage investment and hinder economic growth.

Are there any countries that currently tax unrealized capital gains?

+While several countries have experimented with taxing unrealized capital gains, many have repealed or modified these taxes due to administrative complexities and concerns over their impact on investment and economic growth. France, for instance, has a wealth tax that includes a component for taxing unrealized capital gains on certain financial assets.